One of the best ways to mitigate risk and insulate your organization from malicious actors is to understand where they’re focusing their time and attention as well as leveraging recommended practices to avoid becoming a victim. The recently published CISA 2022 Top Routinely Exploited Vulnerabilities report was compiled with international partners from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the UK and it details the common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) routinely and frequently exploited by malicious actors in 2022 and their associated common weakness and enumerations (CWEs).

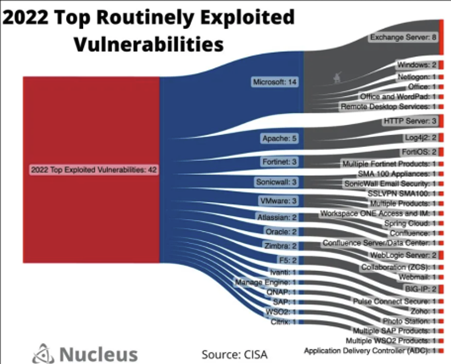

While the report provides a list of the specific top routinely exploited vulnerabilities, it also contains some key recommended broad mitigations and practices that can help mitigate risk from malicious actors’ activities. That said, below is an instructive image from Patrick Garrity of Nucleus Security that provides a visualization of the top 42 vulnerabilities in the report across various vendors and their associated products.

Patrick Garrity/Nucleus Security

Dominant player Microsoft tops list of exploited firms

The top companies experiencing exploits should come as no surprise to anyone who has been watching the industry closely. Widely used Microsoft had nearly three times as many as the second runner up and it also tends to hold the top spot on the CISA Known Exploited Vulnerability (KEV) catalog.

Microsoft has generated headlines in recent months after a widespread incident involving malicious actors from China and vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange that were exploited and impacted the industry as well as the US federal government. The attacks prompted US Senator Ron Wyden to pen a letter to CISA and the US Attorney General, asking that actions be taken against Microsoft for “negligent cybersecurity practices.”

In the aftermath, he Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has announced that its newly formed Cyber Safety Review Board (CSRB), which is made up of various cybersecurity experts and leaders, will conduct a review of the recent incident along with broader concerns around identity and cloud computing due to its widespread systemic risk. This will make it the agency’s third investigation, with the first being on Log4j and the second being on the cybercrime group Lapsus$.

While there’s little to be gained by pointing fingers at any particular vendor or product, CISA’s recommendations for mitigations aimed at vendors, developers, and end-user organizations hold a lot of value.

Mitigations for vendors and developers

In the context of software vulnerabilities and software supply chain security, vendors and developers represent suppliers and — as echoed in sources such as the Cyber EO, and recently published National Cybersecurity Strategy (NCS) — are best positioned to address vulnerabilities.

It’s to be hoped that they heed these recommendations, although it is worth noting sources such as CISA and the CSRB are not regulatory authorities, so these are recommendations, not requirements (unless you’re a software supplier selling to the US federal government and under the purview of publications such as OMB memos 22-18 and 23-16).

Key recommendations for vendors and developers include:

- Implement secure-by-design/default principles and tactics.

- Prioritize secure-by-default configurations.

- Identify repeated classes of vulnerabilities.

- Ensure business leaders are responsible for security.

- Follow the Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF)

These recommendations aim to encourage secure system and software design at the source, starting with software suppliers. This aligns with the latest US National Cybersecurity Strategy (NCS) and language from government cybersecurity leaders striving to push those best positioned to ensure a secure digital ecosystem (software/technology providers) to build security in from the onset, rather than passing insecure products onto downstream consumers. This was also emphasized in a previous CISA publication that focused on secure-by-design/default.

There’s also an emphasis on ensuring secure-by-default configurations, to mitigate the impact of customer misconfigurations or insecure products as soon as a consumer receives and begins using them. Also, by identifying repeated classes of vulnerabilities, vendors can identify root causes in secure system design and development and remediate these issues foundationally.

Cybersecurity helps businesses make good decisions around risk

While we know cybersecurity teams are generally responsible for security, the businesses they serve are accountable for security — cybersecurity is there to help the business make risk-informed decisions, but the business ultimately owns the risk. This means that business leaders must be directly engaged in the security oversight of their organization and risk posture, and this point aligns with recent changes we see from sources such as the SEC in their latest rulemaking.

Lastly, the recommendation to follow the NIST Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) should come as no surprise, as the US government has been advocating for its use for the last several years, since the Cybersecurity Executive Order (EO).

For those unfamiliar, SSDF cross-maps to a variety of industry sources such as the OWASP Security Application Maturity Model (SAMM) and the Building Security in Maturity Model (BSIMM), which focus on secure software development practices and processes. Following SSDF ensures vendors and developers integrate security throughout the software development lifecycle and produce more secure products for customers and consumers.

Cybersecurity guidance for end-user organizations

In the context of software supply chain security, end-user organizations represent downstream customers and consumers. These may be enterprise organizations, SMBs, or even individuals, although the guidance is aimed primarily at formal organizations.

The guidance breaks down recommendations for end-user organizations into subcategories, including:

- Apply timely patches to systems.

- Implement a centralized patch management system.

- Routinely perform automated asset discovery.

- Implement a Zero Trust Network Architecture (ZTNA).

- Supply chain security practices such as asking providers to discuss their Secure-by-Design program or integrating security requirements into contracts.

Some of these recommendations won’t come as any surprise to longtime cybersecurity practitioners, such as the need to apply timely patches or implement a patch management system. However, just because something sounds simple, doesn’t mean it’s easy.

Patching, while a longstanding best practice, is something organizations have struggled with historically. For example, a report shared by the Cyentia Institute recently suggests that the average organization only has the capability and capacity to remediate one out of 10 vulnerabilities in their environment in a given month, leading to an exponential increase of vulnerability backlogs as time goes on.

Another notable recommendation that is a longstanding security practice is having an accurate asset inventory. This is one that has been a CIS Critical Security Control for years, however, organizations struggle to maintain an accurate asset inventory and the problem has only been exacerbated in recent years due to factors such as SaaS sprawl, ephemeral/dynamic cloud-native workloads, and the explosion of the use of OSS components.

CISA gives a nod to zero-trust network architecture

We also see the call for the use of a zero-trust network architecture (ZTNA), which has been an industrywide trend over the last several years, despite being a concept that has been around for over a decade. Zero trust has gained tremendous traction in both the public and private sectors, as organizations look to shift away from the legacy perimeter-based security model and instead leverage zero-trust principles, such as those contained in NIST 800-207 Zero Trust guidance.

Finally, we see the advocacy for software supply chain security practices for end-user organizations. Software supply chain security has continued to be a critical topic in the industry, with some reports projecting 742% growth of software supply chain attacks over the last few years.

Recommendations here include activities such as integrating secure software supply chain requirements into contracts with vendors and suppliers, such as requiring notifications for security incidents and vulnerabilities (vulnerability disclosure programs).

There is also a recommendation to request vendors and third-party service providers provide a software bill of materials (SBOM) with their products to empower transparency for end-user organizations and consumers around vulnerabilities in their environments.

The final recommendation is to ask software providers to discuss their secure-by-design programs. While it is incredibly unlikely that anyone except the most mature and well-equipped software providers has an intentionally secure-by-design initiative, this recommendation is an attempt by CISA to utilize market factors such as customer demand to force software vendors to begin integrating secure-by-design/default principles into their product development. If customers begin to demand something, it becomes a competitive differentiator for vendors who provide it.

While there’s no silver bullet in the world of cybersecurity, retrospectively looking at the behavior of malicious actors can help inform future defenses. The CISA guidance is a great insight into those malicious activities, as well as providing key recommendations for both vendors and developers and end-user organizations to lead to a more secure software ecosystem and society.