The more you do to force people to protect systems and data, the greater your security — that appears to be the assumption some organizations make when addressing cybersecurity problems. However, adding technological hurdles and increasing complexity only creates bad user experiences without effectively improving security.

It is possible to provide a better user experience without compromising security. Here are the six most common user experience mistakes organizations make with security and advice for avoiding them.

1. Not educating employees to develop a cybersecurity mindset

You can’t secure your organization without buy-in from your employees. You can’t get that without making people aware of the risks and the solutions they are expected to use to manage that risk. It’s not something you can leave in the hands of your IT or security specialists, as all employees need to be involved to maintain security. “You have to train people and build a deeper, more effective cybersecurity mindset,” says Yehudah Sunshine, a consultant and expert on cybersecurity influencer marketing.

The challenge here is to communicate effectively with your non-experts in a way that they understand the “what” and “why” of cybersecurity. “The goal is to make it practical rather than condescending, manipulative, or punitive,” Sunshine says. “You need to take down that fear factor.” So long as people have the assurance that they can come clean and not be fired for that kind of mistake, they can help strengthen security by coming forward about problems instead of trying to cover them up.

Sunshine suggests introducing cybersecurity training as a long-term benefit to both the individual and the company. Those involved have to understand that it is important and relevant to people across all departments. Anyone who interacts with vendors, partners, and customers can end up leaving a trail of information that could be used by hackers. That’s why all employees need to be made aware and trained to be proactive.

That’s why it is necessary for companies serious about “building a deep-seated culture that centers around cybersecurity to get buy-in from everybody,” Sunshine says. That includes representatives from HR, UX, and engineering, “as well as someone who can translate the essential concepts into a language that people can understand.”

Companies willing to put in the effort and take a proactive stance without trying “to cut corners” will get better results. Sunshine contrasts that with the ones that only “plug in the holes” that have come to their attention. “They are not committed to actual security –only to saving face.”

2. Believing security is one-size-fits-all

To achieve optimal results, you have to strike the right balance between the level of security required and the convenience of users. Much depends on the context. The bar is much higher for those who work with government entities, for example, than a food truck business, Sunshine says.

Putting all the safeguards required for the most regulated industries into effect for businesses that don’t require that level of security introduces unnecessary friction. Failing to differentiate among different users and needs is the fundamental flaw of many security protocols that require everyone to use every security measure for everything.

Likewise, when it comes to a bank’s activation of security checks on a customer’s online activities, Joseph Steinberg, author of Cybersecurity for Dummies, says it’s a mistake to demand extra codes and proofs of identity for everything the customer does online even if it’s just checking a balance. Treating every action as requiring extra security actually makes people less likely to pay attention to signs of real threats, effectively reducing protection.

What is required depends on the level of risk and the deviations from normal behavior. That could be related to the form of request, the device, the location, or even the keystroke pattern associated with the individual. “When the risk level is low, and the confidence level is high,” Steinberg insists, there is no need to add an extra layer of security. However, you want extra protection if the risk is higher due to the nature of the transaction or a lack of confidence due to the circumstances.

For example, Steinberg says, if the customer always logs in from New York City on a Verizon phone with a particular browser, seeing that customer suddenly use an Apple phone in California should register as a “nonmatch of metadata.” It doesn’t necessarily prove someone is hacking in, but it warrants some form of extra check that the customer should appreciate is meant to keep their account safe.

3. Believing that increasing complexity means increasing security

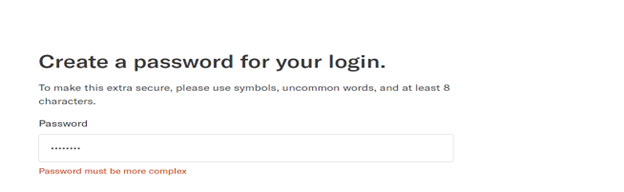

Doubtless, you’ve seen these instructions: “Your password must be eight characters that include at least one uppercase and one lowercase letter plus a number.” Others demand even more specifics as shown below. All this demand for greater complexity is born out of the belief that introducing more variables into a longer combination sequence makes the code harder to crack for hackers.

Ariella Brown

While that is true in theory, in practice, Steinberg explains, the patterns humans fall into make these passwords follow a predictable pattern of starting with a capital, continuing with lowercase letters, and ending with a number with the special character added after that where required. As a result, introducing those additional variables doesn’t make the password as elusive as one may have thought.

Complexity itself causes security problems, Steinberg says. Committing such long, complex sequences to memory is difficult, so they will tend to write them down on paper or store them in their browser. To keep passwords secure, “Passwords should never be stored in plain text or saved in the browser. Instead, they should be in a password manager” that verifies the user with a passcode or through some other means,” says April McBroom, a software engineer and instructor with expertise in cybersecurity.

Some accounts force users to change passwords at set intervals. People don’t tend to think of completely unique passwords for each round, and the slight modifications on their existing password are easy to guess for those who have already hacked the previous version. Users who rely on their own memory are at risk of being locked out of their accounts for mis-entering their passwords too many times. That does not result in a good user experience.

McBroom explains that businesses often substitute passcodes for passwords in combination with a push notification or an authentication app coming through a smartphone. For many businesses, the default form of multi-factor authentication (MFA) has become the code sent to the customer’s registered smartphone number, which introduces pitfalls of its own.

4. Believing that a code sent to the user’s phone is a security panacea

Just like within a company, you should differentiate the levels of security necessary for customers depending on the level of access. However, in the past couple of years, banks have come to require a code sent via text for just about every point of access — even just to check account balances. While that may seem to be nothing more than a minor annoyance to the customer, it can lead to serious problems in both access and security. Some AT&T phone subscribers (including the author) can’t receive these texts on a phone, even after texting messages to the designated numbers to grant permission.

Those who use other carriers can find themselves cut off from that option when they travel abroad, where American SIM cards fail to work. Even worse is that failing to meet the demand for the code puts the customer at risk of having their account frozen, which would cut them off from ATM access. Are all those potential downsides worth it for the extra security obtained from the phone code? Not so, as criminals can get these codes through multifactor authentication fatigue attacks, phishing campaigns, a SIM swap, or other methods.

5. Relying on security questions

When it comes to answering security questions, you can be wrong even if you are right, leading you to be locked out by the automated system. That happened to me when I had to answer the question “Who is your favorite author?” I used the right name, but it didn’t match the record for which I had put in the last name alone, as in Austen rather than Jane Austen.

In place of traditional security questions, Steinberg recommends knowledge-based, particularly with a couple of degrees of separation to make it more difficult for hackers to find the information. For example, for someone who has a sister named Mary, he’d recommend the multiple choice “Which of the following streets do you associate with Mary?” where one of them is a former address.

Steinberg admits, that drawing on such data requires obtaining the legal right to it, which can also be expensive for a business. While Experian, for example, would be able to access it, they would charge for it.

6. Failing to understand the upside and downside of biometrics

When people suggest a passwordless future, some envision biometrics as replacing them with greater security. Fingerprints have been used in place of passwords, though they “can be a tricky situation,” according to McBroom, and can lead to more user frustration if a bug prevents the print read from going through and so fails to grant access to someone who needs it.

Even if they function as intended, Steinberg identifies two major drawbacks to relying on biometrics such as fingerprints, iris or face scans, or voice recognition. One is that a criminal could, say, easily lift fingerprints off anything the authorized person has handled — sometimes even the device itself — to gain access. The other is that once that happens, you can’t just reset fingerprints the way you do passwords.

As McBroom suggests, biometrics can be helpful “on devices that require in-person presence, such a personal work machine or laser-eye reading data for labs.”

Another supervised context for biometric identification is at airports. In Israel, Sunshine says, citizens scan their biometrically enhanced passports in a machine rather than queuing for an hour-plus to be seen by a person like their American counterparts must do in JFK.

Some biometrics are not obviously visible. Behavioral biometrics rely on, for example, the individual’s pattern of typing in the keys used for a password at a set pace with slight pauses between certain letters. Adding that invisible layer that can be encrypted and stored alongside the encrypted password enhances security, according to Steinberg.

“Invisible biometrics are better than what one can see,” Steinberg asserts. That brings up one final mistake that people make when it comes to the user experience: They assume security is about the things they see when — like icebergs — most of it should be beneath the visible surface. “The less the user has to see, the better,” Steinberg says. That is the key to minimizing an adverse effect on the user experience.