In a year full of national elections, security pundits and practitioners are focused on the shape of influence campaigns in 2024. With more than a third of the world’s population heading to the ballot box in more than 50 elections worldwide, the threat of disinformation powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and shaped by a tense international arena feels more significant than in years past. In the West, government officials have voiced concerns about the political process involving controversial candidates and issues, where the impact of novel attacks such as compromise of polling systems or use of deepfakes to suggest vote tampering might amplify insecurity.

Recent research by this author and his colleagues in the Journal of Cybersecurity offers a fresh take on one kind of digital threat to democracy that is often overlooked or mislabeled — that of cyber-enabled influence operations (CEIO). Conversation about the information threat to democracies in 2024 often centers on cyber influence operations or election hacking. These discussions often conflate two separate kinds of interference and compromise. Influence operations involve attempts to degrade, corrupt, or subvert the national information environment for gain. Cyber operations involve disruption, espionage, and subversion of information infrastructure.

Our research engages the idea that CEIO exist, but we often don’t clearly see what they might mean for our democracy because we tend to overfocus on acts that are more one thing than the other. In particular, we clarify the character of CEIO by studying the footprint of foreign-backed malign information operations. Attacks on voting infrastructure or high-profile compromise of politically relevant systems are often less effective at aiding influence campaigns than they sound. Instead, malware deployed to enhance the spread of social network connectivity and disinformation presents as a critical feature of sophisticated influence operations. It can overcome constraints faced by foreign malign actors and amplify attempts to reach broad sections of Western population.

How influence and cyber operations differ

How do cyberattacks aid attempts to generate influence? Many experts argue that they really don’t. The logic of each activity for political purposes is quite different. Cyber operations, while occasionally used to degrade national security capabilities, typically follow the format of intelligence operations in that they emphasize access, compromise of systems, and secrecy to achieve strategically valuable goals (e.g., IP theft or performative sabotage). Influence operations manipulate and corrupt information conditions to achieve persuasive effects (e.g., for political deception or distraction).

While there are similarities, the operational shape of cyber and influence operations ends up being quite distinct. Both need secrecy for success, for instance. With influence operations, however, secrecy matters much more after an attack is launched due to the need to sustain effects. The opposite is generally true for cyber activities. Likewise, while cyber operations subvert systems by making them act in ways not intended, the mechanisms of doing so are syntactic or rely on narrow social engineering attacks.

Access, in other words, is possible via manipulation of tangible systems. Influence operations also seek to subvert but “compromise” and “access” are psychological outcomes, at least above the level of campaign tactics. You can hack a social media account, but actual influence requires shaping the information environment via less direct methods of sociopolitical messaging. This is made harder by the attacker’s need to avoid revealing themselves and risk the credibility of an influence operation’s messaging, which is not always true for cyber activities.

Cyber-enabled influence: What does it look like?

For the past decade, experts have pointed to ways in which cyber and influence operations can sometimes enhance one another. These fall into four categories:

- Preparatory operations are activities that leverage the intelligence potential of cyberattacks to enhance the potential of a subsequent influence campaign. Those actions include reconnaissance, resource (e.g., botnets) creation, account takeover, directed capacity denial, and targeted sociopolitical compromise.

- Manipulative attacks are intended to create influence in themselves (e.g., by compromising voter systems).

- Attacks in parallel involve cyber activities leveraged against a nation simultaneously with influence activities without clear operational coordination.

- Influence-enabling attacks reverse the conventional logic of CEIO and see interference activities leveraged to augment the sociopolitical impact of cyber operations.

Until recently, research on cyber and influence operations deployed in tandem has mostly focused on manipulative and parallel attacks. There are several reasons for this. Influence-enabling activities focused on the psychological impact of cyber operations come with many operational complications and are likely to be rare.

Evidence about preparatory attacks is much more difficult to come by in the public arena than more visible operations against national infrastructure or political targets. Until recently, national security practitioners believed that preparatory cyber actions are never what makes influence operations strategically relevant and so are less worthy of focus.

Direct manipulative attacks or attacks in parallel to influence operations activities, by contrast, aligns with the warfighting mentality that has driven more than two decades of thinking on cyber operations as tools of statecraft: Visible attempts to interfere in foreign states might have clear signaling value.

The utility for spreading malign influence is unclear, and this is the issue with a focus on CEIO that emphasizes cyberattacks conducted in visible formats. Attacks against election infrastructure may have minimal effects on citizens’ trust in election integrity, but they add little value to more subtle attempts to shape public attitude.

This prompts a question as to whether manipulative attacks are distinct from operations conducted in parallel. If they present as a separate form of influence activity, then they are not truly an exercise in influence enabled by cyber. While cyber threats to political processes have had minimal impact on the decision-making of political elites, they aren’t as clear signals as attacks on military targets or other kinds of critical infrastructure.

New evidence malware-enhanced influence campaigns

Our recent research breaks new ground in understanding how cyber operations, particularly the use of malware, can expand the scope of influence campaigns. Using sophisticated model techniques, my colleagues and I examined the content of Russia’s Internet Research Agency’s (IRA) influence campaign on Facebook during the Russian Federation’s 2014-2016 interference campaign in the United States in an attempt to answer a simple question: What drove the IRA’s targeting? The results were remarkable, illustrating a threat lifecycle driven by the outsider-looking-in dynamic of malicious influence operations and involving the novel use of malware to further the spread of malign influence.

As many researchers have noted, there are clear trends in the content the IRA deployed on Twitter, Facebook, and elsewhere in the campaign to interfere with the US 2016 presidential campaign season. These include a focus on African American communities and race issues alongside discourse on police brutality, Second Amendment issues, and more conventional content (e.g., video game and sports conversation). Why these topics? What drove variation in how content was posted over time? Explanations for the IRA’s targeting efforts include that the Russians were working from the content of the one-time intelligence leak orchestrated by Paul Manafort or were just focused on the most divisive issues of the day.

We began with an alternative idea rooted in the logic of influence operations: The need to avoid attribution means that influence operators must use organic developments in their target nation as a foundation for finding an audience. Using AI techniques, we found that Facebook ad content was published in a particular order. Regardless of whether the focus was Black Lives Matter (BLM) or pro-law enforcement issues, we saw scaremongering content published in one period and then replaced by messaging encouraging users to take action.

Not only does this parallel conventional political messaging, this pattern of appealing to fear first and then action second appeared and reappeared directly in line with domestic triggering events. After both incidents of and rallies against police violence, for instance, the messaging cycle would begin anew.

This confirms that sophisticated malign influence activities rely on developments in a target nation to generate initial interest without compromising the identity of the attacker. Perhaps most interestingly, our research also unexpectedly uncovered evidence of malware being leveraged against Facebook users.

While it may seem counterintuitive that the IRA would hack users that they are trying to influence without being caught, the operational approach here was clear. They used click-fraud malware like FaceMusic to infect an initially gullible population, enhance the visibility of troll farm content used by IRA accounts, and then expand the reach of the influence operation to more diverse social media populations. Given the focus in CEIO research on direct attacks on influence infrastructure like voting systems or social media platforms, this finding is revelatory.

Capture, not kill: Operational utility feeds strategic value of cyber-enabled influence operations

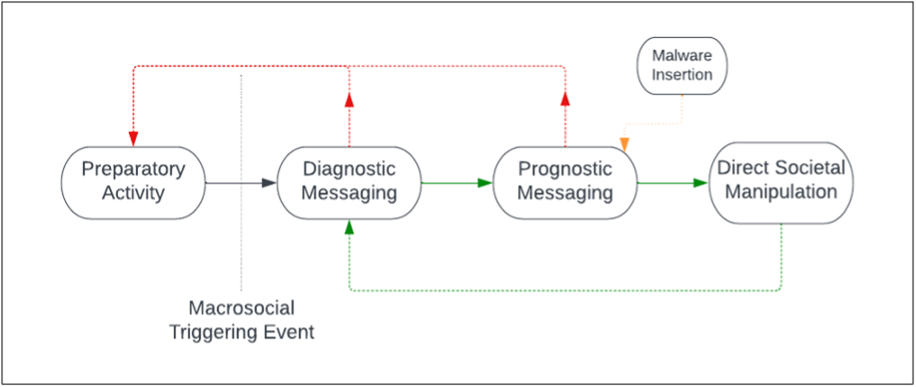

This research shows a clear lifecycle of CEIO activities that is rooted in a robust understanding of the constraints facing influence operators. We might think of this as a capture chain rather than the traditional kill chain. As the diagram below shows, preparatory cyber activity is critical in the development of influence campaigns that can be the differentiator between tactical results and strategic value. After a belligerent like the IRA establishes its initial social media footprint, it engages in a messaging campaign that references domestic triggering events to engage and capture an initial population.

As with much social engineering, however, the first-mover principle with influence operations is to target gullible persons to expand access. Malware was the key to this goal, translating the prospects of the operation from one with limited likelihood of serious impact to something capable of generating strategically meaningful manipulation of America’s information environment.

Christopher Whyte

This new take on the use of malware for influence operations not only refocuses research and practice on CEIO, it also helps make sense of high-level empirical patterns in the marriage of cyber and influence efforts in the past couple of years. As Microsoft and other technology stakeholders have noted recently, for instance, there is a clear difference in practice between Chinese and Russian and Iranian threat actors in this space since 2020. While Chinese APTs have been linked to numerous influence campaigns, the use of malware or more performative cyber actions alongside such efforts is minimal, particularly against Western targets. By contrast, hackers backed by Moscow and Tehran consistently blend the methods, to questionable results.

A promising explanation for this divergence lies in the character of Chinese influence operations, which have often focused on the West more on issue-based manipulation of media and less on subverting sociopolitical systems. Such an approach relies much more on distraction and on generating noise than it does on targeted audience effects. As such, the utility of malware is less.

Assessing cyber-enabled influence operations vulnerability

How should security teams assess risk around cyber-enabled influence? The conventional answer to this question is similar to assessing risk from geopolitical crisis. When considering the threat of manipulative or parallel cyber activities, vulnerability is most significant for two types of actors. First, any organization whose operation directly ties into the function of electoral processes is at heightened risk, whether that be social technology companies or firms contracted to service voting infrastructure. Second, organizations that symbolize key social or political issues are at risk of compromise as foreign threat actors seek to leverage contemporary conditions to produce performative ends.

This new research, however, suggests that risk lies much more problematically with workforces than with organizations themselves. The use of malware against vulnerable populations on social media suggests that the CEIO threat is much more disaggregated than national security planners and industry security teams would like.

Traditional hygiene controls like workforce training and constraints on the use of personal equipment are obviously key to limiting organizational vulnerability to infection. More generally, however, the notion of a capture chain emphasizes yet again the need for sociopolitical intelligence products to be factored into security analytics. Assessing CEIO risk means not only understanding how geopolitical circumstance heightens company vulnerability, it means understanding when personnel background and practice introduces new risk for organizational function.